Female Genius: Carmen Herrera

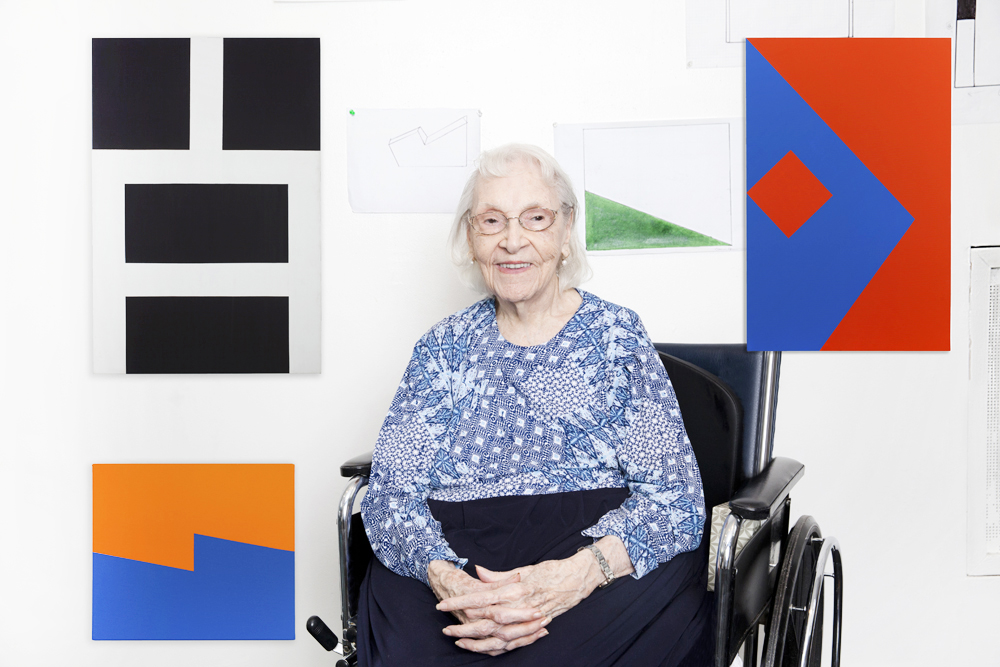

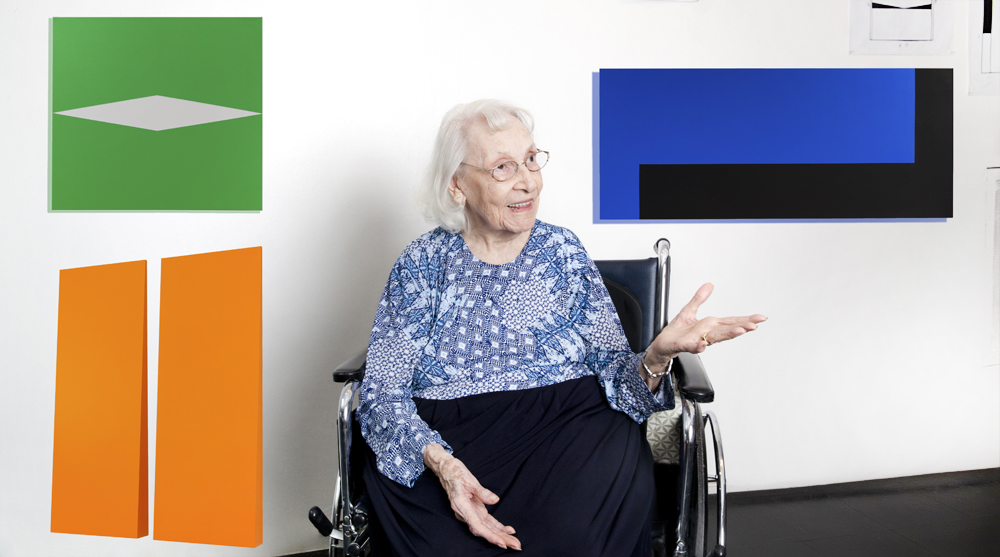

For most of her one hundred years, the Cuban-born painter Carmen Herrera has lived in a creaky, third-floor loft in Manhattan’s Flatiron district, working in near-total obscurity. She had to wait until 2004 to show in a New York gallery, and until 2009 for her first sale—to the collector Agnes Gund, then president of the Museum of Modern Art. Herrera was 90. (The artist Tony Bechara, a close friend and longtime supporter, had introduced Gund to work by Herrera in a 1998 exhibition at El Museo del Barrio.)

That same year, coincidentally, the Ikon Gallery in Birmingham, England gave Herrera’s distillate, geometric abstractions a solo outing. (The gallery’s Nigel Prince had been Googling Arturo Herrera and found her instead.) The show brought her a still-growing tide of admirers who have a hard time believing that someone who painted with such authority and refinement could escape notice for so long.

Indeed, even Barnett Newman, a friend and artist whose austere verticals and pure colors would seem to have made him a natural ally, was not aware of her work. “We used to have breakfast with him and his wife every Sunday,” Herrera told me, when I visited, accompanied by Bechara. (“Carmen doesn’t hear so well now,” he said. “But she’s used to the sound of my voice.”) Most of the place was devoted to workspace. Only the library of aging books at one end of the loft signaled that it had also been home to her late husband, Jesse Loewenthal, a New York City schoolteacher who was twenty years her senior and also long-lived: he died in 1998, at 100.

I asked if Newman had ever paid her a studio visit. “Never,” Herrera replied from the wheelchair that gets her around now. “We never talked about art.” That was astonishing. “I didn’t understand English,” she explained, “so I would just sit there.” Newman was also more than a generation older. His friendship was actually with Loewenthal, who met the artist when both students were at City College, at the time a bastion of Jewish intellectuals and radical thought.

Loewenthal met Herrera on a visit to Havana in the 1930s, sent to her door by a brother, who was working at NBC radio in New York. The couple married in 1939 and spent the Second World War in Manhattan, where Herrera took classes at the Art Students League from a teacher who did not understand abstraction. She did not flourish.

The Loewenthals moved into their loft in 1954, on their return from a nearly five-year sabbatical in postwar Paris, where Herrera became a pal of the Cuban painter Wilfredo Lam. It wasn’t her first time in Paris. In 1929, when she was fifteen and “a fat little thing,” she attended a Parisian convent school. Much to her pleasure, she saw both Josephine Baker and Edith Piaf perform, but wanted to be like Greta Garbo. Not alone, but thin. “The only way to do that,” Herrera said, “was to eat nothing. The nuns never paid any attention.”

Because of her previous experience in Paris, she had no difficulty with the language the second time around. She struck up a friendship with the writer Jean Genet, who took her to the world premiere of Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot. “The theater erupted in argument,” she said, “but Genet was the sweetest person in the world.” “But Carmen,” Bechara interjected. “He was a violent man who spent most of his life in prison.” “I’m sorry,” Herrera protested. “To me he was sweet. And he was my friend.” Unfortunately, he never saw her paintings either.

But she was exhibiting—with the Salon de Réalités Nouvelles, an association of abstract artists who came and went, mostly not to be heard from again. “Weren’t you friends with Marie Raymond, the mother of Yves Klein?” Bechara asked, hoping to jog a crowded memory. “Oh, yes!” she exclaimed. “She was very French. She was married to a painter who opened a school for girls, very beautiful girls.” He left with one of them.

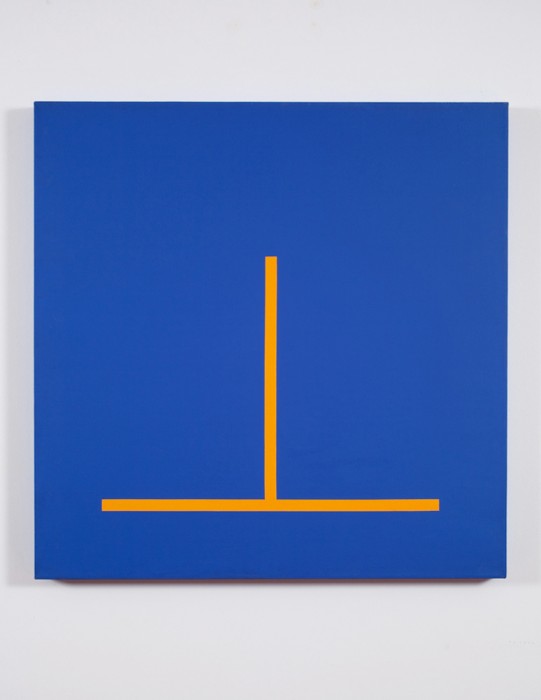

Though she met Mondrian—“not the most cheerful person in the world”—Herrera was not painting in proto-Minimalist style then. Curving shapes floated around the murky palette of her canvases like feathers in the wind. When she was accepted for the salon’s inaugural exhibition, Fredo Sidès, an organizer with Robert and Sonia Delaunay and Nelly van Doesburg, gave her a critique. “Oh, Madame,” he said, “you have many paintings in this one!” “He was being polite,” she said. “He was trying to tell me I was doing too much.” She started paring down. By the early ’60s, she had created “Blanco et Verde,” a series of diptychs, each of almost breathtaking simplicity: green isosceles triangles, some hardly more than a thin line, on broad white fields. (In the fall of 2016, the series will form the nucleus of her retrospective at the Whitney Museum, her first major solo exhibition in a major American institution.)

In Paris, she also met Mark Rothko through his assistant, Theodoros Stamos, a former pupil of her husband’s. “We invited him to dinner and to go to the theater,” she said of Rothko. “It was so sad. He never wanted to do anything. Then he went back to the United States and killed himself. He had a big name. I don’t know why he did it. We could see there was something wrong, and we couldn’t do a thing for him.”

Until they returned to New York, the Lowenthals lived frugally, mostly on a pension from Herrera’s father, the founding publisher of the newspaper El Mundo, who died in the Cuban War of Independence in 1898, when Herrera was only four. His star reporter was her mother, who died in the 1960’s, after Fidel Castro closed the paper. “She was Cuba’s first feminist,” Bechara said. “To be a woman journalist in 1900 Havana was very advanced.” Herrera nods. “In Cuba, they always called my mother ‘the American,’” she recalled, “because she was tall and always dressed up. My father was crazy about paintings. We had a very important collection. We had to sell it to keep going after he died. Why are we talking about my father?” she asked then, temporarily lost in the narrative of her long, colorful life.

She wanted to be an artist but enrolled at the University of Havana to study architecture, “Because I liked it,” she said. Because the school was closed most of the time by political unrest, she joined an informal group of students to study from books they imported from Europe. After her marriage, Herrera never returned to Cuba. She has not forgiven the Castro government for keeping her brother in prison for five years. She won his freedom by appealing to a great uncle who was an influential cardinal in Spain. “The family hoped he would become Pope!” she said, laughing.

The usual, now clichéd explanation for Herrera’s lack of recognition through decades of steady work, is that there was no market for female artists in the 1950’s, when the white boys’ club of Abstract Expressionists defined the New York School. “They drank a lot,” Herrera recalled. (Remember how long Joan Mitchell, Louise Bourgeois, Louis Nevelson, Agnes Martin, and Elaine de Kooning suffered minority status—years—causing Mitchell, de Kooning, and Martin to leave New York.) But other factors figured in Hererra’s isolation from the art community, too.

If women artists had a hard time in those days, Latina women had it worse. Most were ghettoized as folk artists and Herrera wasn’t that. What’s more, her pristine planes of simple geometries, which she painted in her choice of only one or two rich colors (with white or black) were out of step with the gestural pyrotechnics of the Ab-Ex generation, if not with younger and better known Minimalist artists like Ellsworth Kelly and Agnes Martin. Strangely, she didn’t know either one. Nor did she have much to do with Alfonso Osorio, her downstairs neighbor, or meet her fellow Minimalist Sol LeWitt, who lived a few doors away. The reason? She didn’t hang out—not with the Pop and Conceptual artists, who were unknown to her circle with the devoted Lowenthal, a different crowd. So they never walked the two blocks to Max’s Kansas City, the primary watering hole of artists in the ’60s. “I knew a lot of people,” Herrera said, but they weren’t in the art world, and only a few were friends.

She’s outlived all of them, but her husband’s death was the most difficult to survive, and it ruptured a lifelong daily practice. “Then,” she said, “one day I picked up a pencil.”

Herrera isn’t sad anymore, even though she can no longer go out for walks in her now fashionable neighborhood. She reads books, draws, makes paintings, and has a couple of drinks. “I picked up a pencil,” she said again, “and began drawing.” “You remember that day?” Bechara asked. She nodded. “I remember,” she said.

Linda Yablonsky is a New York-based writer and the author of The Story of Junk: A Novel. She has written for The New York Times, Artforum, and W Magazine.

This story originally ran in PIN-UP Magazine, Number 19. Special thanks to Eva Kenny and Nadine Johnson.