Lynn Hershman Leeson in Venice: Logic Paralyzes the Heart

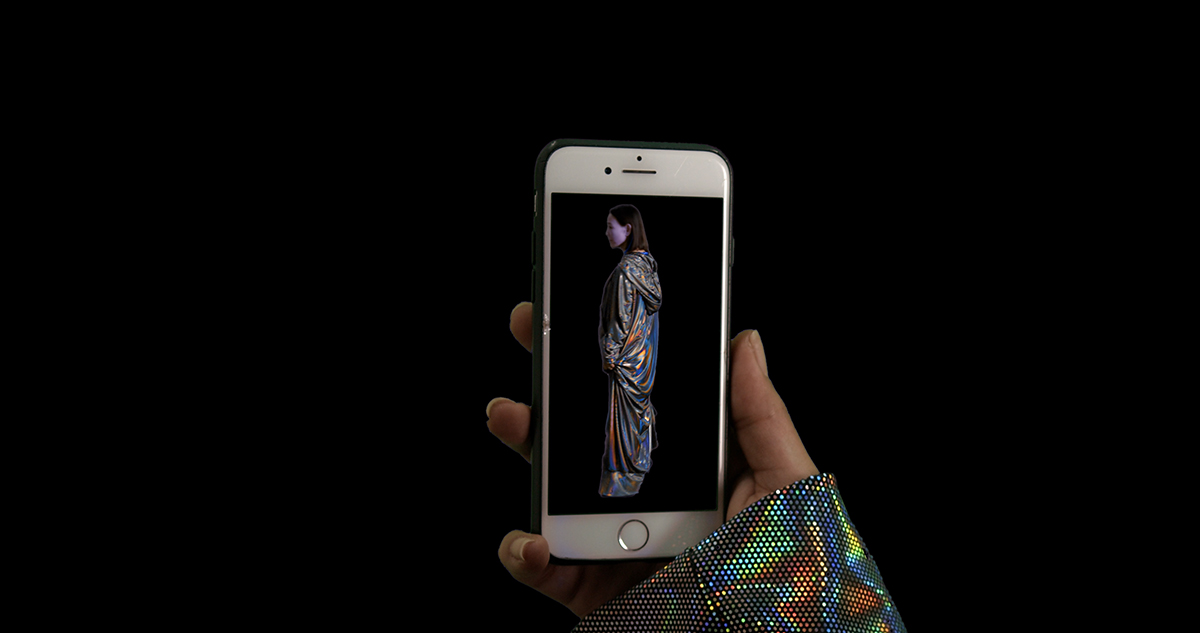

Joan Chen dressed by Nin Hollein.

“The cyborg is now 61 years old—and having a mid-life crisis.” This is one of many provident zingers from Lynn Hershman Leeson. With a lingering pandemic and a new war in Europe raging, the long-awaited 59th Venice Biennale undoubtedly, at least in part, addresses so many of the drastic changes that the world has undergone in the past few years. In her contribution to the Biennale, Hershman Leeson proposes that the evolution of the cyborg has reached a new turning point, bringing a heightened sense of complexity to the whole affair. The Venice debut of the artist’s video installation, Logic Paralyzes the Heart (2022), has won her a distinguished special mention from the Biennale’s jury, confirming the entangled and all-encompassing narratives that she so adeptly reconfigures continue to resonate with audiences and discourse alike.

The international group exhibition, curated by Cecilia Alemani and titled The Milk of Dreams (a direct reference to the children’s book of the same name by surrealist artist Leonora Carrington), opened unusually early last month, and has been lauded for its history-making majority of women or gender-non-conforming participants. It is clear from the title that the overarching theme in Venice this year, much like the themes Hershman Leeson has meditated upon throughout her multidisciplinary practice, hinges on the progressively blurred distinctions between what is real and what is artificial, innate and ersatz. But what Hershman Leeson brings to such a global discussion of how advancements in technology and media continually change human behavior is made all the more auspicious when taking into account the foreboding kinds of omens embedded within her sprawling body of work. Gliding into the seventh decade of a career filled with brazen examinations of the personal and collective lenses through which identities (and in particular women’s identities) are wrought and mangled, and with an intimate knowledge of the notion of cybernetics—which is central to The Milk of Dreams—Hershman Leeson has developed a singularly canny perspective within this context.

The artist has also noted that she was the first to depict and refer to “the cyborg” in her work, in 1963—just three years after the term was coined by NASA. Since then, she has continually found new ways to traverse the questions and issues raised by the interloping of the machine into the corporeal. In this way, Hershman Leeson has been central to expanding our understanding of the prismatic concept of the cyborg as it has matured alongside the artist’s own practice. From GMO-bred glow-in-the-dark cats to the primary-colored clones of Tilda Swinton in the feature-length AI-jaunt Teknolust (2002), and so many other projects in between, Hershman Leeson’s far-ranging practice has parsed the contentions between humanity and technology. Through all of the different ways that this examination has taken shape over the years, her work illustrates, again and again, the myriad schemas through which this perhaps never before so germane, shape-shifter cyborg has manifested itself within contemporary art, culture, and science. With all this at her back, Hershman Leeson’s intimacy with the subject at hand leads viewers to trust her most revealing caricature of this mercurial figure that is embodied in Logic Paralyzes the Heart.

As it turns out, the cyborg (at least in Hershman Leeson’s iteration) is Joan Chen! The luminous actress is best known for playing the mysterious and devilishly duplicitous Josie Packard in the original Twin Peaks television series. Josie pretends to fall in love with the town’s trusty Sheriff, Harry S. Truman, but as it turns out she had been manipulating both him and her sawmill-owning husband, Andrew Packard. Her backstory, revealed toward the end of the show’s two-season run, is that Josie had actually set the industrial fire that sent her late husband to perish in the flames, in order to collect his insurance money from the mill.

With Chen taking center stage, so to speak, the installation of Logic Paralyzes the Heart is positioned in the last section of the Biennale’s Arsenale, where works that investigate technology and cybernetic themes are brought together. Here, the video of Chen’s cyborg is projected in a black box next to an entryway room lined with custom Hershman Leeson wallpaper depicting a vast array of faces. In the video, we learn from Chen that the faces presented are not those of real people, but are computer-generated and amalgamated into a pastiche of AI image segments. After a brief recap about the coinage of the term “cyborg” and a caveat pointing out that its progenitors were “convinced that ‘THE CYBORG’ was an interface to human liberation,” the single-channel video opens with Chen as an anthropomorphized brainchild—of course—seen through the glassy screen of an iPhone. It seems that, whoever this incognito heroine might actually be, she is also the character holding the very phone within which we are now, finally seeing her. A moment later we are zoomed onto a close-up of her face and see that it is overlaid with a transparent, geometrical symbol, while a jumble of letters runs across the bottom of the screen, like a chyron in stereotypical LCD (Liquid Crystal Display) font.

As the blurry contours of her face come into focus, she begins to self-reflexively chronicle her operational past and hopeful future. She gives an oral history of her superpowers: her chameleon-like transmutability, her use of “deep fakes,” her AI “ancestors,” as she refers to them. It becomes clear, if it wasn’t already, that war, conflict, and espionage are central to her origins. At one point Chen is joined by actress Tessa Thompson, of HBO’s Westworld (talk about cyborgs!), who appears briefly as an educator of sorts who lays out this sordid history. Chen then links the use of predictive codes for battle-planning within technologized warfare to the use of similar codes by local police forces, who retool them in order to hone crime zones for government surveillance.

Hershman Leeson’s work has always exposed what lurks beneath the surface, conjuring what we think we see. Yet at the same time, her research and information-based practice is ultimately an exercise in the dissection of tiny pieces that make up a whole. Her Venice Biennale debut is no exception. The installation is as much a warning about the future as it is a cryptic reflection of where we’ve been. Hershman Leeson once stated that she “considers the rapid developments of biotechnologies to be the central challenge of our age.” The enmeshment between the natural and the mechanical realms has remained critical to her practice, despite the distinctions between them having inflated over time. By giving a face, a voice, and a body to the otherwise shadowy cipher of the cyborg, Logic delves right into the origins of where those two sides of the metaphysical coin first met.

Logic Paralyzes the Heart is not the first Hershman Leeson work to illustrate the ways that technological incursions into daily life and human behaviors has signified the furthering fruition of the cyborgian idea of the body, (whether individual or collective), being overtaken by machinery. She has always been at the forefront of applying whatever the newest modes of tech have been, within their time, into works of art. While her practice has spanned a range of materiality, it has, nonetheless, remained rooted in how we perceive ourselves and others as these technologies incrementally seep more and more into the ways that we live and communicate. This began in the 1960s, when Hershman Leeson’s work often took the form of drawings on paper that then mutated into experiments with Xerox machines. Continuing the trajectory of introducing mechanics into otherwise traditional artistic presentations, her later forays into sculpture were rendered composite by incorporating simplistic machines like tape players, as well as more complex devices like sensors. Through the ’70s and ’80s, as increasingly enigmatic technologies became more accessible, these artistic developments continued to shift, with Hershman Leeson picking up the camera and using photography to achieve what at that time appeared to be unusual and nuanced perspectives. It is poignant to note that during this time, while technology became more and more entrenched within both the subject of Hershman Leeson’s work and the processes through which she conveyed her ideas, her work moved more and more off the page, outside of the white cube, and into “the real world.”

This is perhaps best exemplified by her axiomatic, identity-defying performance project, Roberta Breitmore, whose official duration ran from 1973–78, but whose concepts continue to recur throughout Hershman Leesons’s practice. The original project marked her creation not just of a character, but of an actual alternate identity. Breitmore’s being was made “real” with official records like a temporary driver’s license, credit cards, apartment leases in her name, and even dental records and psychoanalysis session notes. These materials validated her supposed existence, despite her having been “played” by a number of proxies, including Hershman Leeson herself.

By the time Y2K rolled around, Hershman Leeson’s work had begun to focus on bio-politics. This is perhaps most comprehensively presented in her extensive, eight-room project, The Infinity Engine (2014), wherein she created an emblematically antiseptic, lab-like environment made up of a partially interactive, multimedia installation that included genetically modified fish, a 3D printed “human” nose, and a series of video interviews with doctors focusing on regenerative medicines and the human genome. By legitimizing Breitmore’s identity through the cataloging of medical records, in particular, Hershman Leeson’s foresight proved shrewd. This lays bare the underlying reality that the panopticonic structure within which we ALL exist is, at its core, based not on one’s name, or even social security number, but on our blood, our very DNA!

Two years into the COVID-19 pandemic, we have become far more familiar with the concept of vaccines and bio-politics than many of us would prefer. Hershman Leeson’s 2021 work on paper, Vaccine Terror, which was on view in her most recent solo gallery exhibition, About Face, in March 2022 at Altman Siegel in San Francisco, addresses this reticence. Here a daintily etched ink drawing depicts a Big-Brother-esque hand hovering over a much smaller woman’s face, poking at it with a sharp object, where, just at the point of contact between the two, a scribbly caption reads, “VACCINE TERROR!” It is telling that Hershman Leeson has said that her “best work [has come] on the cusp of disasters.” As we continue to face the disaster that is this pandemic, and accept, if reluctantly, the fact that we will likely be receiving annual booster shots of these new-fangled, MRNA-based antibodies, we see the pith of Hershman Leeson’s work at every level. This intuition on her part extends to reflections of other ways that the pandemic has changed how we live and interact as well. In another work on view in About Face, a self-portrait titled QR Identity Finder (2022), a QR code square is overlaid onto the face of the artist. This image, taken in her home, unsarcastically features in the background a sign that reads “pitalism.” Additional letters are cut off, but we see just enough of the word to make it apparent that it could allude to nothing else. Here, Hershman Leeson again nods to the unforeseen side effects of the pandemic and the odd measures we’ve gone to in order to keep our distance from everyone and everything. Hence the QR code works as a stand-in for all kinds of objects and places that we would normally experience in person, but now access via our phones, which are never not in our hands.

Courtney Malick is an art writer and curator whose work focuses on video, new media, sculpture, performance, installation and the intersections therein. She contributes to publications such as Flash Art, CURA Magazine, and Kaleidoscope, among others. Malick’s forthcoming memoir, L.O.T.P. (Life of the Party), chronicles the antics of downtown Manhattan in the early and mid aughts, just as smartphones and social media would change being young and partying forever. L.O.T.P. dishes on the ensuing cultural wasteland of post-internet art and the slew of artists, designers, DJs, models, and actors that dominated the city’s sordid and glittering nightlife.